Reflections on “How to build a sustainable future”

Blog follow-up to the “How to build a sustainable future” talk, given in Stafford 13 May 2025 by Professor Alison McMillan

Last week, I gave an evening seminar talk entitled “How to build a sustainable future”. Being that the audience was expected to be predominately comprised of local members of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, I assumed a baseline understanding of the issues of Climate Change.

Assumed prior knowledge

In short, I assumed that it was generally known and understood that the increasing (but very low) concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere is predominantly caused by human burning of fossil fuels; and that the rise in CO2 concentration causes heat to be trapped by the atmosphere, leading to global warming. Furthermore, that this effect has been measurable and recorded over the past half century, and that the relationship between CO2 concentration and average global temperature is firmly established.

A more sophisticated understanding would recognise that the “Net Zero by 2050” target (whether achieved or not) is an attempt limit the further increase of CO2 concentration. The purpose of this is to limit the average global temperature rise, because climate modelling suggests that irreversible unstable run-away effects, called “tipping points” will ensue if global average temperatures exceed 1.5 or 2 °C. Some of this modelling might be considered inexact or incomplete, but the evidence of increasingly extreme weather patterns, ice loss from the poles, and sea water temperature and pH changes are undeniable.

Purpose and outline of the talk

The purpose of my talk was to pose a re-think about the way in which we use energy. Currently, the thinking is to replace fossil fuels with something else, for example replacing petrol cars with EVs. This makes a difference, but is it enough? Does the tactic of substitution create new problems? Another way to address the issue is to reorganise the way we live and run our society, so that less energy is required.

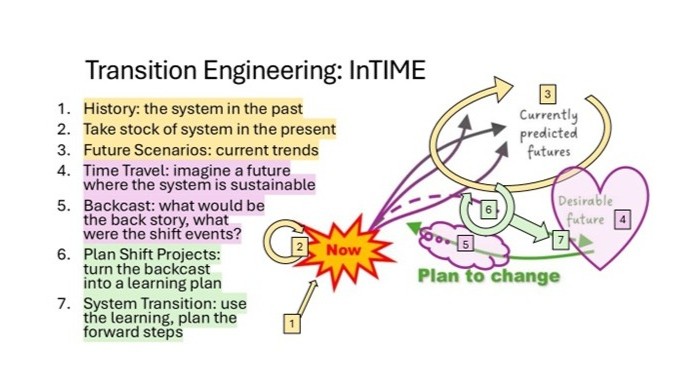

I outlined the Transition Engineering InTIME process – see the figure above. The first three activities (highlighted in yellow) are typical of engineering design and problem-solving: review how similar problems have been solved before, consider the current requirements and context, and consider future implications. In the context of climate change future predictions, working with the best current engineering capability, but maintaining current societal behaviours, we will exceed the “tipping points”.

What if we were to change society? Can we change it in such a way that quality of life can be maintained, but achieved differently? This requires imagining a new and desirable future, and then imagining how to make the changes necessary to get there (steps 4 and 5, highlighted in pink). Imagination is the domain of artists, but the goal is a desirable future for everyone. For this reason, the activity is a “co-creation” – artist speak for engaging the community or other groups in the creation of an artwork. Such a future would have to work: it needs to be functionally achievable, and it needs to be a place where people are happy.

Making that desirable future achievable, and then driving the processes of getting there, are again part of the engineering domain. Steps 6 and 7 are highlighted in green, to indicate that although the activity would be led by engineers, it would be achieved through ongoing co-creation with the artists and the communities.

In conveying these thoughts, I suggested that the InTIME process can be applied to one’s own life, such as when considering career changes. Given the urgent needs of action for climate change, it could be timely to consider lifestyle changes in alignment with this. “Cognitive dissonance” isn’t exactly an engineering concept, but in the pursuit of personal happiness, a big step is to reconcile one’s personal values with one’s life choices.

Learning outcomes

The learning outcome for me was that, even among those whom one would expect to have a baseline of prior knowledge, there are some who are ill-informed. I was shocked to learn that there are engineers who do not recognise that the (albeit small) changes to the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere, used by human action, are on the brink of destabilising the planetary climate balance. We have all seen the memes on social media, with their misinformation and denialism: I was amazed to hear engineers repeating these back to me during the Q&A. If it is widespread that professionals in Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths (STEM) are repeating such misinformation as dogma, then it is little wonder that decision-makers and the voting population are confused.

Perhaps I can draw a parallel with the concept of “bias” in Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI). Many who approach EDI training do not believe at the outset that they are biased: it is only in the examination of the implications of assumptions or expectations, that they realise that their actions or behaviours were intrinsically inequitable. For example, choosing venues for meetings, or times of day, that make it harder for some people to participate than others.

In the same way, I started to wonder whether there could be a “bias” in STEM practitioners? One of the markers of professional achievement for an engineer is to hold Incorporated or Chartered Engineer status. There are similar routes for other STEM professionals. Renewal of the status occurs annually, based on the principle of Continuing Professional Development (CPD). Now, the focus of that CPD might be in the specialism of the engineer: for example, in improving or updating one’s capability in Computer Aided Engineering. The bias comes from confusing specialist knowledge with general professional competence. Perhaps there should be a directive to include more social and societal aspects?

Next steps?

I will champion the review of CPD guidance and processes within STEM organisations. It isn’t feasible to enforce any belief system on an individual, but members of STEM organisations should be encouraged to avail themselves of a minimum level of knowledge and understanding of significant societal issues. Both Climate Change and EDI are significant societal issues, and probably there are others. The CPD system, coupled with assessed approval for Chartered status renew, could be a means to ensure that happens.

It's not just what we know that counts, but what we recognise we do not know.